Handley Page Victor - History

Handley Page, after the success of their wartime Halifax bomber, soon looked at new designs for better bombers and a tail-less swept wing aircraft was one of their pet projects. Attracting the interest of the Air Ministry, by the start of 1947 an official specification (B.35/46) was issued to cover the development of this new aircraft, designated by Handley Page as the HP.80, after initial design of a type designated the HP.75. It would be one of three V-bombers, the others being the Avro Vulcan and Vickers Valiant. The intention was to get the aircraft into service by 1951, this showing how little idea the Air Staff had of the task they had laid before the various V-bomber manufacturers.

Handley Page decided to test their crescent wing and tail design on a smaller aircraft. A Supermarine type 510 fuselage (basically an Attacker fuselage, designated type 521 by Supermarine) was bought from Supermarine and after a brief stay at General Aircraft, moved onto Blackburn where it was married to appropriate crescent-shaped wings and a T-tail, becoming known as the YB.2, or HP.88. Coded VX330, it actually flew too late to be of much use in the Victor programme and was lost in an accident on August 26th, 1951, killing HP pilot, Duggie Broomfield.

HP.80 WB771 - the first Victor prototype; Handley Page

By mid-1952 the first HP.80 was ready to fly but had to be transported by road to Boscombe Down as Handley Page's airfield at Radlett had too short a runway. In June an order for 25 aircraft was placed, the official name of Victor being bestowed at this time. After re-assembly the first HP.80, WB771, flew on Christmas Eve. Differing a lot from the initial tail-less design of the HP.75A, it now had a large T-tail but retained the crescent wings (so designed to keep a constant critical mach number throughout the wing's length). Compared to the Vulcan and Valiant, the HP.80 had a much larger bomb bay and a very different crew compartment. On the Vulcan and Valiant the crew compartment was smaller, caused by it being a single sealed unit with pressure bulkheads fore and aft. On the Victor the pressurised crew compartment extended right to the tip of the nose, giving more room and a better view for the pilots. However, the undernose radar was in an unpressurised compartment so the cockpit floor was higher, with the rear crew at almost the same level as the pilots instead of lower down (actually the pilots are slightly lower on the Victor).

In common with the Valiant and Vulcan, only the pilots had ejector seats. While the initial design had included an escape capsule enclosing the entire crew area, the Air Ministry had changed its mind by 1950, no doubt due to the costs of such a system. So instead the pilots got ejector seats, and the rear crew died if there was an emergency. The first HP.80, and the second (WB775) were soon found to have some problems, particular a mis-positioned centre of gravity. While lead weights sorted this out in the first two, future examples had a lengthened front fuselage. This also had the bonus of allowing the crew more chance of escape; originally the engine intakes were so close to the crew door that escape was a very risky business. Now it was marginally more safe (and there were some successful escapes later on).

HP.80 WB775 - the second Victor prototype

Test flights proceeded relatively smoothly with only minor mishaps occurring, until July 14th 1954. WB771 was carrying out a low level calibration run over the runway at Cranfield when the tail ripped off and the aircraft crashed, killing the crew. A combination of mistakes in calculations had led the engineers to believe there would be no problems with the tailplane, when in actual fact the three bolts holding it on were subject to more stress and fatigue than expected, especially when the tail began to flutter. The second HP.80 had its tail fitted using four bolts and flew on September 11th 1954, appearing at the Farnborough SBAC show during this first flight! By the end of the year all trials were completed and the aircraft was handed over to the A&AEE for further testing. The Victor B.1s on the production line were given smaller tails to counter the fatigue problem that had destroyed WB771. In May 1955 a further 33 Victors were ordered. Handley Page's test pilots had fun with their new aircraft - after test flights over the North Sea they would often 'forget' to tell Air Traffic they were coming back, which they did at maximum speed and altitude in a dead straight line for the UK. The only fighters in the country that could intercept them (and regularly did) were the American F-101 Voodoos of the 81st TFW. A shameful tale in terms of RAF defence capability of the time - but it showed how impressive the Victor was.

Artist's impression of the HP.111; Handley Page

By early 1956 the first Victor B.1 had finally come off the production line, and flew on February 1st. Fitted with more powerful versions of the Sapphire engines used in the HP.80 prototypes, the Victor's cleared maximum speed of mach 0.95 soon proved to be a little on the pessimistic side when test pilot Johnny Allam inadvertantly achieved mach 1.1 in a one to two degree dive! Deliveries to the first RAF unit (232 OCU) began in November 1957, and Bomber Command became operational with the Victor in April 1958 (10 squadron being the first operators). Few changes were considered necessary to the exceptionally trouble-free airframe, limited only to weight-saving changes to the outer wing to reduce the leading edge's complex droop (replaced with rather less attractive vortex generators on the top of the wing). Changes in the second production batch to expand the tailcone's size to make room for tail warning radar along with revised pressure cabin and engines brought about a change in designation to B.1A. Victors were soon part of the nuclear deterrent, initially carrying the Yellow Sun hydrogen bomb. The success of the type prompted Handley-Page to offer a transport variant to the RAF - the HP.111 - but sadly for HP this never saw fruition.

By late 1955, though, Handley Page had put forward proposals for an improved Mk.2 variant (not that the Victor needed much improvement) and soon the B.2 began to take shape. Despite the future of bombing obviously lying in the low-level under-the-radar attack, the B.2 was to be a 'fly higher, fly faster' design (in fact, it would beat the Vulcan in this respect). With the much higher thrust Sapphire 9 engines cancelled in the usual lunatic manner of the Air Ministry's dealings throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Rolls-Royce Conways were instead earmarked for the Victor B.2. Much redesign of the wing roots, intakes and engine boxes was required but eventually the B.2, with extended wingspan (made up from an insert in the wing and a larger wingtip), changed tailcone, all-new electrical system and many other modifications, was finally put into production. The first B.2 flew in February 1959. In August one was handed to the A&AEE but disappeared over the Irish Sea on a test flight; while the cause for the crash has never been proved for sure, most evidence pointed towards a simple pitot tube failure, resulting in the Mach Trim stut extending fully and eventually causing a mach 1+ dive into the sea.

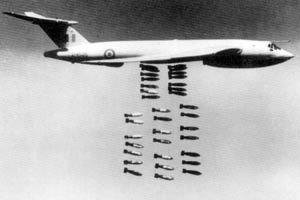

B.1A XH648 releasing 35 conventional 1000lb bombs

The B.2's role was soon changed to that of low-level bombing, and with appropriate green and grey camouflage replacing the earlier anti-flash white, the B.2 force also began carrying the Blue Steel nuclear missile. The American Skybolt missile now came into the picture; the government was keen to add this to the V-force's arsenal and accordingly cancelled several Victors already in production! The reasoning being that a Victor carrying four Skybolts (two under each wing) was doing the job of four Blue Steel-carrying Victors, and therefore fewer were needed!

B.2 carrying Blue Steel nuclear missile; Garry Lakin's collection

By this time Handley Page was in trouble; the government's plan to merge all the aircraft manufacturers into fewer companies and order only from these larger bodies meant that BAC and Hawker Siddeley were the preferred manufacturers. Handley Page had not merged with anybody, and further Victor orders were looking increasingly uncertain. The government then reinstated the cancelled Victors with promises of 27 more if only Handley Page would go ahead and merge with somebody. In the middle of negotiations with Hawker-Siddeley, 22 Victors from the promised 27 were cancelled. The production run cut short in this manner, the final B.2 rolled off the line in April 1963 and delivered to the RAF in May.

Sir Frederick Handley Page, on his deathbed, railed at the destruction wrought by the mandarins of Whitehall, saying "The misguided little men think they are having their revenge". He would die without ever seeing the collapse of his beloved company, a small mercy at least. 1963 also brought the first hint of action for the Victor; deployed to Singapore in December as a show of force when Indonesia threatened the British protectorate of Malaysia. Indonesia backed down when further Victors were deployed to the area, but the V-force remained a regular visitor from then on, usually in the shape of Vulcans.

B.1A(K2P) XH648 refuelling Lightning F.6 XR768, 1967; MoD

Meanwhile the B.1s and B.1As had given sterling service and when the B.2 began replacing them, the decision was taken to convert the Mk.1s to three-point refuelling tankers, designated initially BK.1 and BK.1A (later K.1 and K.1A as they were no longer capable of bombing); the Valiant was serving in this role but was not ideal and sooner or later would need to be replaced. In the middle of the work to convert B.1s to K.1s (in January 1965), the Valiant force was suddenly grounded after massive fatigue fractures were found in the main spars of many aircraft. Low-level operations had badly fatigued the Valiant which proved unable to cope with the stress of this new environment, and suddenly the RAF was without its Valiant tankers. With the need for the Victor tanker now urgent, six B.1As were taken out of service for a rush-job - conversion to two refuelling points, both from pods under the outer wings (the other Victors would have a centreline point as well). The first converted aircraft flew on April 28th 1965 and the RAF had regained its tanker force by August, with 55 Squadron being the first operational Victor BK.1A unit (receiving its first example in May). Later this two-point version would be redesignated the B.1A(K2P) as it was still capable of being used as a bomber, and to distinguish it from the three-point tankers. 57, 214 and 19 Squadrons followed with the three point K.1s and K.1As.

SR.2 XM715 showing off the reconnaissance pack in the bomb bay; MoD

Despite the lack of new-build Victors, Handley Page still had plenty of work to do on the Victor force - a reconaissance variant was needed, so building on the experience gained in fitting radar reconaissance equipment to a few B.1s, nine B.2s were produced to B(SR).2 standard. These were B.2s basically built to Blue Steel standards (with large drag-reducing fairings known as Whitecombe Pods or Krucheman Carrots on the wings, which doubled up as useful space for defensive countermeasures equipment, rapid start system, Conway 20101s, underwing tanks and fixed droop leading edges). The Blue Steel mounts were not needed and the bomb bay was filled with cameras and powerful photoflashes. The B(SR).2 proved to be an exceptional reconaissance platform and gave useful service for around eight years before being retired; three were then converted to K.2 standard.

The cancelled Victors were now proving to be a costly mistake; the tanker force was at the edge of its capability and the K.1As were nearing the end of their useful life. More tankers were desperately needed. HP had produced a feasibility study for a Victor K.2 in 1967, which the MoD had accepted but the MoD delayed singing the contract until Handley Page collapsed and went into liquidation in February 1970. The job of the K.2 conversions was instead given to Hawker Siddeley - in fact, the old Avro team at Woodford, Handley Page's old rivals. They disregarded many of the planned K.2 modifications (e.g wing tip fuel tanks) and instead cut the wing span and moved the underwing pods further out. Other changes resulted in a Victor that performed rather poorly compared to previous versions (though it still outperformed many other aircraft including jet transports). The work was substantial (involving complete dismantling, replacing parts of the spar and removing much existing bombing/ECM equipment) and cost the MoD millions more than HP's study had suggested, as HSA had no experience in the Victor and had a steep learning curve to overcome. However, the K.2 was still an extremely useful tanker. Entering service in May 1974, 1975 saw yet more cancellations in the defence review of that year. In the end only 24 conversions were carried out, and were planned to fly for the next 14 years until around 1988.

The Victor tankers would see action twice; first of all, in 1982. The Argentines invaded the Falkland Islands and when a show of strength was required, Strike Command put forward a plan to fly a single Vulcan to the islands and bomb Port Stanley's runway in order to deny the Argentines the chance to use it for attack aircraft. One problem - the Vulcan had nowhere near enough range to get to the Falklands from the nearest useable airfield (Wideawake on Ascension Island) and back. Inflight refuelling would be necessary - and a lot of it.

K.2 displaying the three refuelling hoses and drogue units; Garry Lakin

The famous Black Buck missions were at the time the longest undertaken in the history of air warfare; the refuelling plan called for no less than 11 Victors to take off with the single Vulcan, with the Victors refuelling both the Vulcan and other Victors in order to get the Vulcan and a single final Victor to the last refuelling point. There the Victor would refuel the Vulcan for a final time before the attack. Victors would once again be waiting to refuel the Vulcan after the attack took place; five being needed for the return trip. On the first mission, the final pre-attack refuelling revealed the bravery of the Victor crews, when the Victor gave the Vulcan enough fuel to continue, but left itself short - and they would not break radio silence to request a tanker to meet them on the way home; without being refuelled itself, the Victor could not make it back to base. Thankfully after the Vulcan had broken radio silence as planned to announce a successful attack, they could get another Victor scrambled and waiting when they neared home. While the Vulcan missions were long, so were the Victor missions of course - and not just when supporting Black Buck missions. On one occasion, XH675 carried out a reconnaisance mission, radar mapping the South Atlantic on a mission lasting 14 hours and 45 minutes and covering a distance of 7,000 miles! The surge in Victor operations required to support the war in the South Atlantic meant, of course, a shortage of tankers at home. To continue to meet commitments in the UK and Europe, several Vulcans were converted to K.2 standard with a single HDU box scabbed on to the rear fuselage (the ECM bay being gutted to cater for the extra equipment needed). Unfortunately the Falklands operations (which continued until 1985 when a new larger airfield - RAF Mount Pleasant - was built in the Falklands) also used up a lot of the Victor's remaining fatigue hours (sortie rate being 30 times the peacetime norm), so by 1986 a number of Victors were retired and 57 squadron was disbanded, leaving only 55 squadron.

K.2 XH672 seen at RAF Finningley (Battle of Britain display 1993) with Maid Marian artwork, mission markings and 'I RAN OFFUTT!' door artwork; author

Life passed quietly enough for the remaining Victor tanker force until 1990, when Saddam Hussein's forces invaded Kuwait. On the eve of retirement in early 1991, Operation Granby (the RAF's designation for Gulf War operations) brought forth the ageing Victor to fly in support of allied sorties into Kuwait and Iraq. Of the eight Victors involved in Granby, six gained colourful and risque nose art (courtesy of Cpl. Andy Price of 55 Squadron) and were named after crew chief's wives and/or girlfriends. Refuelling not only RAF aircraft, but also other allied aircraft including US Navy types, the Victor put in sterling service as usual. Mission markings (small petrol pumps) applied to the participating aircraft included, on one, an unusual 'kill' - one Victor banged into a vehicle incorrectly parked and not seen by the Victor crew. Cue one kill marking! Later in the US at Offutt AFB, another Victor suffered a slight mishap, running out of taxiway - appropriate artwork was soon applied on the cockpit door!

End of the line - XM715 finishing a fast taxi run at Bruntingthorpe; author

The Victor force really distinguished themselves in the Gulf, with 299 sorties tasked and 299 carried out - a 100% availability rate not matched by any other RAF aircraft. Despite this brief spot in the limelight, the Victors were reaching the end of their lives and were being increasingly replaced by VC-10s (another Conway-powered aircraft of course, which had been in RAF service since the early 1980s). Retirement finally came on 15th October 1993 when the last Victor squadron, 55 Squadron, disbanded at RAF Marham. Most Victors ended up in use as firefighter training aids or were scrapped, only a few being preserved. Of the 86 Victors produced (including the two prototypes), only 5 full examples now survive. Of 55 Squadron's last seven serviceable examples, three went for BDR/crash rescue training (all since scrapped), three were preserved and one was scrapped with the nose allocated to the RAF Museum. A further unserviceable example and assorted hulks were scrapped. Two of the survivors are capable of fast taxi runs, and this led to an inadvertent flight by the Bruntingthorpe example, which took to the air briefly in May 2009 - and thus became the last Victor flight ever.

Leading Particulars

| Variant | HP.80 | B.1(A) | B.2 | B.2R | B(SR).2 | K.1A | K.1 | K.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First flight | 24th Dec 1952 | 1st Feb 1956 (B.1A 18th Jul 1960) | 20th Feb 1959 | 19th Feb 1962 | 23rd Feb 1965 | 7th Dec 1965 (B.1A(K2P) 15th Apr 1965) | 2nd Nov 1965 | 1st Mar 1972 |

| Crew | Two to five - pilot, co-pilot and sometimes flight test engineers | Four to six - Pilot, Co-pilot, Air Electronics Officer, Navigator Plotter, often Navigator Radar and optionally Aircraft Servicing Chief on a jumpseat. | ||||||

| Armament | None | Blue Danube or Yellow Sun nuclear bombs, Blue Steel nuclear missile (B.2 only), 1 x 2,000lb, 1 x 7,000lb, 21 x 1,000lb or 35 x 1,000lb bombs | F49, F89 and F98 cameras and up to 108 photo-flares in 3 containers | None | ||||

| Powerplant | 4 8,0000lb Armstrong- Siddeley Sapphire 101 | 4 11,050 lb Armstrong-Siddeley Sapphire 20201/20701 | 4 17,250 lb Rolls-Royce Conway 10101 | 4 19,750 lb Rolls-Royce Conway 20101 | 4 11,050 lb Sapphire 20701 | 4 19,750 lb Rolls-Royce Conway 20101 | ||

| Max. speed (at 34,000 ft) | 225 knots (mach 0.9) | 645 mph (1,038 km/h) (mach 1+ in a shallow dive) | 610 mph (982 km/h) | |||||

| Service ceiling | 49,000 ft (14935 m) | 55,000 ft (16,764 m) | 49,000 ft (14,935 m) | |||||

| Range | ? | 2,700 miles (4,345 km) | 4,600 miles (7,400 km) | Probably more than B.2 | Similar to B.1 | Similar to B.1 | 4,500 miles (7,242 km) without using transfer fuel | |

| Empty weight | 70,000 lb | 89,000 lb | 98,000 lb | Similar to B.1 | Similar to B.1 | 114,050 lb | ||

| Max. take off weight | 105,000 lb | 180,000 lb (81,650 kg) | 223,000 lb | 185,000 lb | 238,000 lb (107,957 kg) | |||

| Wing span | As B.1 | 110 ft (33.53 m) | 120 ft (36.58 m) | 110 ft (33.53 m) | 117 ft (35.66 m) | |||

| Wing area | As B.1 | 2,406 sq ft (223.5 sq m) | 2,597 sq ft (241.3 sq m) | 2,406 sq ft (223.5 sq m) | 2,580 sq ft | |||

| Length | 111 ft 7 in | 114 ft 11 in (35.30 m) | 114 ft 11 in (35.30 m) | 114 ft 11 in (35.30 m) | 114 ft 11 in (35.30 m) | |||

| Height | 26 ft 10.5 in | 28ft 1.5 in (8.59 m) | ||||||

Data for HP.80 prototype is for WB771 as it first flew. Both it and WB775 were modified during their testing careers. Question marks on HP.80 data may be similar values to those of the B.1. My thanks to Roger Brooks of the HP Association and Vladimir Stanojevic for their beyond-the-call-of-duty efforts in researching some of the data here.